1968 protests at Columbia University called attention to ‘Gym Crow’ and got worldwide attention

Stefan M. Bradley, Loyola Marymount University

“If they build the first story, blow it up. If they sneak back at night and build three stories, burn it down. And if they get nine stories built, it’s yours. Take it over, and maybe we’ll let them in on the weekends.”

This is what Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Black Panther Party affiliate H. Rap Brown told a crowd of Harlem residents at a community rally in February 1967.

They were there to protest Columbia University’s construction of a gymnasium in Morningside Park, the only land separating the Ivy League university from the historic black working-class neighborhood. The gym, along with the discovery that Columbia was affiliated with the Institute for Defense Analysis – a national consortium of flagship universities and research organizations that provided strategy and weapons research to the U.S. Department of Defense – stirred students to protest for more decision-making power at their elite university.

When considering the key events of 1968, such as the Tet Offensive, the assassinations of national leaders, demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention and the Olympics, as well international events concerning democracy, the Columbia uprisings merit attention.

Issues converge on campus

As I detail in my book – “Harlem vs. Columbia University: Black Student Power in the Late 1960s” – all the issues of the 1960s and New Left collided on the Morningside Heights campus of Columbia. Students contended with the war in Vietnam, institutional racism, the generational divide, sexism, environmentalism and urban renewal – all while trying to find dates and attend classes.

Everything came to a head on April 23, 1968 – just weeks after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. That was when members of the Columbia chapter of Students for a Democratic Society hosted a rally on campus to decry the war – and, what many considered the racist gym in Morningside Park. Members of the Students’ Afro-American Society, or SAS, and Columbia varsity athletes – known as jocks – were in attendance as well. SAS followers showed up to resume an earlier fight they had with the jocks who supported the construction of the gymnasium.

Read more: Revolution Starts on Campus

Some students had been working with Harlem community groups. They saw the gym as a symbol of the university’s “power” over a defenseless and poverty-stricken black neighborhood. They joined local politicians who opposed the gym for a myriad of reasons, including its concrete footprint in a green park and the inability of the community to have access to the entire structure once built.

Troubled relations

The situation was, of course, complex. Columbia had long been a contentious neighbor to Harlem and Morningside Heights. The campus gym was decrepit and prevented the university from competing with its Ivy peers effectively in terms of facilities and space. Regarding the park, Columbia had constructed softball fields that initially community members could use. By 1968, however, only campus affiliates could access the fields. Then, white faculty members had been mugged in the park.

The university, seeking to expand in the postwar period, purchased US$280 million of land, mortgages and residential buildings in Harlem and Morningside Heights. That resulted in the eviction of nearly 10,000 residents in a decade, 85 percent of whom were black or Puerto Rican.

Columbia acted in coordination with Morningside Heights, Inc., a confederacy of educational and religious institutions in the neighborhood that also sought to “renew” the area to serve their mostly white patrons. David Rockefeller, grandson of oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, acted as MHI’s first president. Columbia was the lead institution.

Despite being close to a black neighborhood, the university admitted few black students and employed a handful of black instructors. For instance, as I report in my book, in the 1964-1965 school year, there were only 35 black students out of 2,500 students enrolled in Columbia’s College of Arts and Sciences, and just one tenured black professor. By spring 1968, there were more than 150 black students enrolled.

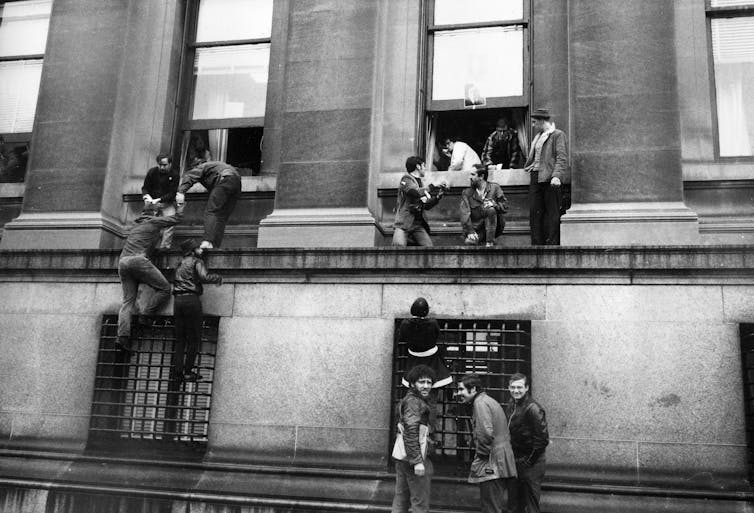

On April 23, protesting students attempted to take over the administration building but were repelled by campus security. Then, they walked to the gym construction site where they tore down fencing and physically confronted police. From the park, they returned to campus where they finally succeeded in taking over a classroom building, Hamilton Hall. In doing so, they surrounded the dean of the college, Henry Coleman, who chose to stay in his office with his staff. To “protect” Coleman, several jocks stood guard outside his door.

Clashes with police

What started as a racially integrated demonstration of students took a turn in the late night when H. Rap Brown and several community activists showed up at the invitation of the Students’ Afro-American Society. The student group, Brown and the community activists agreed that black people solely should occupy Hamilton Hall and that white activists should commandeer other buildings. The white demonstrators accommodated, leaving Hamilton and taking over four other buildings. That forced Columbia officials to contend with not just a student protest but a black action on campus at that height of Black Power Movement. Incidentally, the community activists removed and replaced the jocks as sentries of the dean’s office.

To the ire of many white university administrators of the period, Stokely Carmichael of SNCC and the Black Panthers fame showed up to explain – through the press – that the university deal either with the student activists on campus or militants coming from Harlem. This insinuated the tone of the demonstrations would change drastically. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated less than three weeks before. From offices in Morningside Heights, Columbia administrators had watched Harlem burn as residents mourned and reacted to the black leader’s death. The only thing that separated the elite white institution from angry black rebels was the park in which the university was building a gymnasium against the will of many community members.

In consultation with New York Mayor John Lindsay, Columbia administrators chose to end the demonstrations by calling 1,000 New York police officers to clear the five occupied campus buildings on April 30. Chaos and brutality prevailed. As the NAACP and other Harlem community organizations stood watch, black students vacated Hamilton, which SAS had renamed Malcolm X Hall, and were arrested peacefully. In the building that national Students for a Democratic Society leader and Port Huron Statement author Tom Hayden occupied, police and demonstrators collided physically. One of the most iconic documents of the postwar period, the 1962 Port Huron Statement outlined the need for young people to be in the vanguard of the movement to eradicate racism and grind the military-industrial complex to a halt; it centered the notion of participatory democracy, which called for greater inclusion of the citizenry in decision-making. In other buildings, students found themselves on the hurt end of police batons when they resisted arrest.

Worldwide attention

In opening the door to violence, the university turned what was a local matter into an international story and radicalized moderate students and neighborhood residents. Young radicals abroad learned of “Gym Crow” and university-sponsored defense research. In solidarity, they supported the Columbia student activists’ causes and chanted “two, three, many Columbias” – a refrain that gained popularity among American student protesters.

After the demonstrations in April, ensuing violent demonstrations in May, and a six-week student strike, the university did not build the gym in the park and renounced its membership in the Institute for Defense Analysis.

In my view, elements of the 1968 Columbia rebellion are inspiring and instructional for today’s students, protesters and community residents. As gentrification threatens the homes of poor black people in urban areas today, activists should recall that 50 years earlier young people believed they could cut their university’s ties to war research and prevent a prestigious white American institution from expanding into black spaces at the same time. They succeeded.

Our new podcast “Heat and Light” features Prof. Bradley and Columbia University’s Michael Kazin discussing this issue in depth.

Stefan M. Bradley, Chair, Department of African American Studies, Loyola Marymount University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Recent Comments